What sets it apart: Filecoin’s proof system

Much like other large technological innovations, blockchains are the marriage of several established technologies that have already been used and trusted for decades. “Consensus mechanisms,” studied since the 1970s and developed in the 1990s as a tool to combat email spam, let users in a distributed system come to an agreement without the need for a central arbiter.

Blockchains use different systems to maintain consensus. For example, Bitcoin’s proof-of-work consensus mechanism requires miners to compete with one another to solve a computationally expensive math problem in order to verify payments made between two people exchanging Bitcoin. Solving these problems requires lots of electricity. That’s why you hear reports about the Bitcoin network using more power annually than all of Switzerland (and its consumption growing much faster).

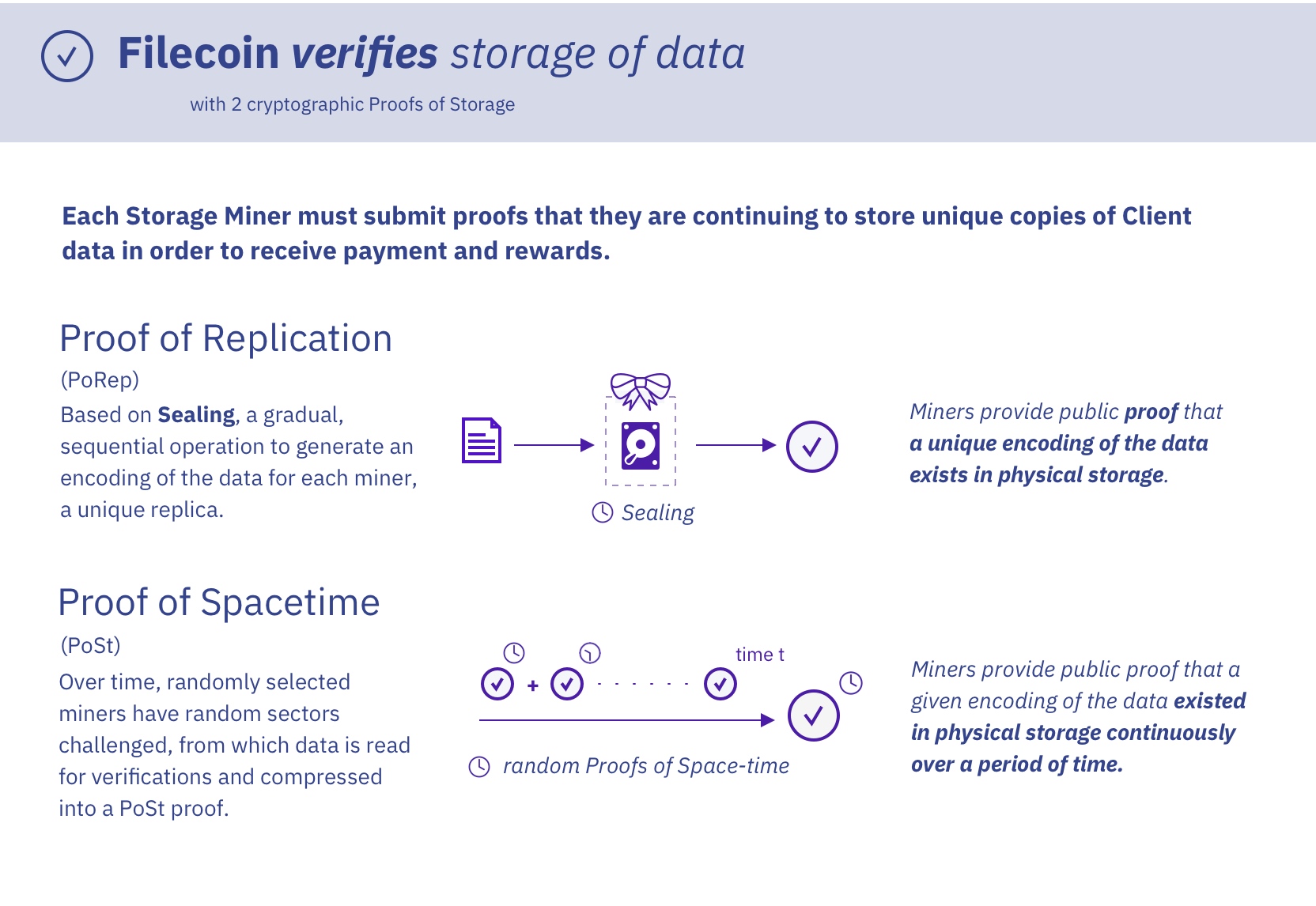

Filecoin is built on a variation of Proof-of-Space. It is also related to Proof of Stake in that instead of only tokens as stake, stake is in the form of proven storage that determines a miner’s probability of mining a block. In building a decentralized storage network, a proof structure was built in which consensus is achieved through an operation yielding positive social externality: data storage. With the testnet launch, a new set of storage-based proof systems has been unveiled to attain decentralized consensus.

When Filecoin was announced in 2017, the plan was to create a decentralized storage network built on a robust decentralized market. To seed this market, to decentralize market functions, and to incentivize early miner participation, a crypto token was created, a byproduct of Filecoin consensus. This token is generated on the back of useful work, namely a useful Proof-of-Replication and Proof-of-Space-time.

The Story of these Proofs

PL’s Juan Benet explored the history of Filecoin’s proof construction in a recent interview on the Zero Knowledge podcast. The following are excerpts from that interview:

“Filecoin pushes the frontier of blockchains in a number of different ways. Proof of Replication is ultimately a proving system to verify that a storage miner actually has the content they are storing and are not cheating. Within these systems it’s a very hard problem: how do you prove to the network that you’re indeed storing something and not just lying about that?

There are other interesting problems Filecoin tries to solve, including things like higher throughput consensus and interoperable, content-addressable linking data structures that Filecoin uses so on. But at the end of the day, it’s all about taking all of the unused storage on the planet and organizing it with incentives, to build the largest, most powerful computing storage network and drive prices for this storage down.

Filecoin’s Proof of Replication is both a Proof of Storage and Proof of Space, and these are subtly different [explained later]. In Filecoin units of data are stored in what are called sectors. You seal specific data in a sector on disk in a slow encoding process and commit a proof of that to the blockchain. Sealing is an intense amount of work spent on that particular proof. In order to fake a proof like that, you would have to do that particular work using the original data that a client stores on Filecoin, unlike numeric hashes in Bitcoin’s Proof of Work.

Proving systems are cryptographic protocols where there’s a prover and verifier and the prover is going to prove something to the verifier. In Proof of Work, for example, it’s that the prover has done some amount of work, or spent some amount of computational cycles. The classic example is hashes [in Bitcoin]. Another example is a Verifiable Delay Function (VDF), where I can prove to you that I’ve spent a certain amount of cycles, in sequence, and so I’ve waited a certain amount of time [Filecoin does not use VDFs but it’s a research area]. So all these Proof of Storage systems are proving systems like that, low-level cryptographic primitives used in a wide variety of protocols.

Proofs of Storage are simple proving systems to prove that I have possession of some data. A Proof of Data Possession example is: I can prove to you that I have data X, either without revealing data X or if the data is several GB large, in some more succinct way. Then there’s Proof of Retrievability where, not only am I going to prove that I have X, but also that these proofs can be used to reconstruct X in case I’m malicious and want to withhold X from you.

Proofs of Space are a different type of group where I can guarantee to you that I’m spending a certain amount of storage. If I commit to storing 1 GB, and I generate a random GB then I can prove to you that I’m storing that random GB and not storing some other thing. That lets you use storage space as a Proof of Work.

The interesting part is combining a Proof of Space with a normal Proof of data possession, where I would like X to be useful, not just a random string. The hard part of this was to create a Proof of Space that was also being used to store useful data. So that’s what Proofs of Replication are as foundational primitives in the Filecoin network’s cryptographic protocol.

Other Proof of Storage systems were invented to create clouds that you could trust better because they could prove to you that they were backing up your data. But they went completely unused in the normal centralized cloud environment where trust is contractual. And now they are being used in the whole decentralization space because this is where we’re using incentives structures to guarantee things not contractual agreements.

We also use SNARKs to prove some of the actual Proofs of Replication which produce large outputs. We’d like to do a lot of challenges on these Proofs of Replication but aggregate them so they can go on chain in a very small, compact way. There are different ways to do this but SNARKs are a great way to do this, they give you a way to prove that you’ve done the proofs correctly, then you can just put the SNARK proof on the chain. Then parties can now verify a few of the inputs themselves and the actual SNARK proof, and know that the proof has been generated correctly.

In Proof of Replication we take the source data, a large amount like 32GB, and apply a very slow encoding that produces these lattice-like graphs in layers where a node might be a 32 byte segment. There’s a sequential process going on producing a graph and for each node hashing sequentially. It has to be done one after the other, because of the hash function.

Now that we’ve done that, in order to prove that we’ve done this encoding correctly, we can either do the entire encoding inside of a SNARK, which would be extremely expensive, or we could just sample a few of the challenges to prove that we have stored this. Say we sample a thousand random challenges over this whole proof, and we do that computation inside of the SNARK. We take the source encoded data, then decode it, and then show that that goes all the way back to root that we committed to. It’s that proof that we want to make succinct. Because otherwise it’d be a 32 byte leaf and then the whole Merkle chain all the way back up to the root would be a pretty large amount of data, then times that by a thousand. 100s of KB or MB to produce one proof. With a SNARK we can compress it down, I think it’s like to 200B or something like that.

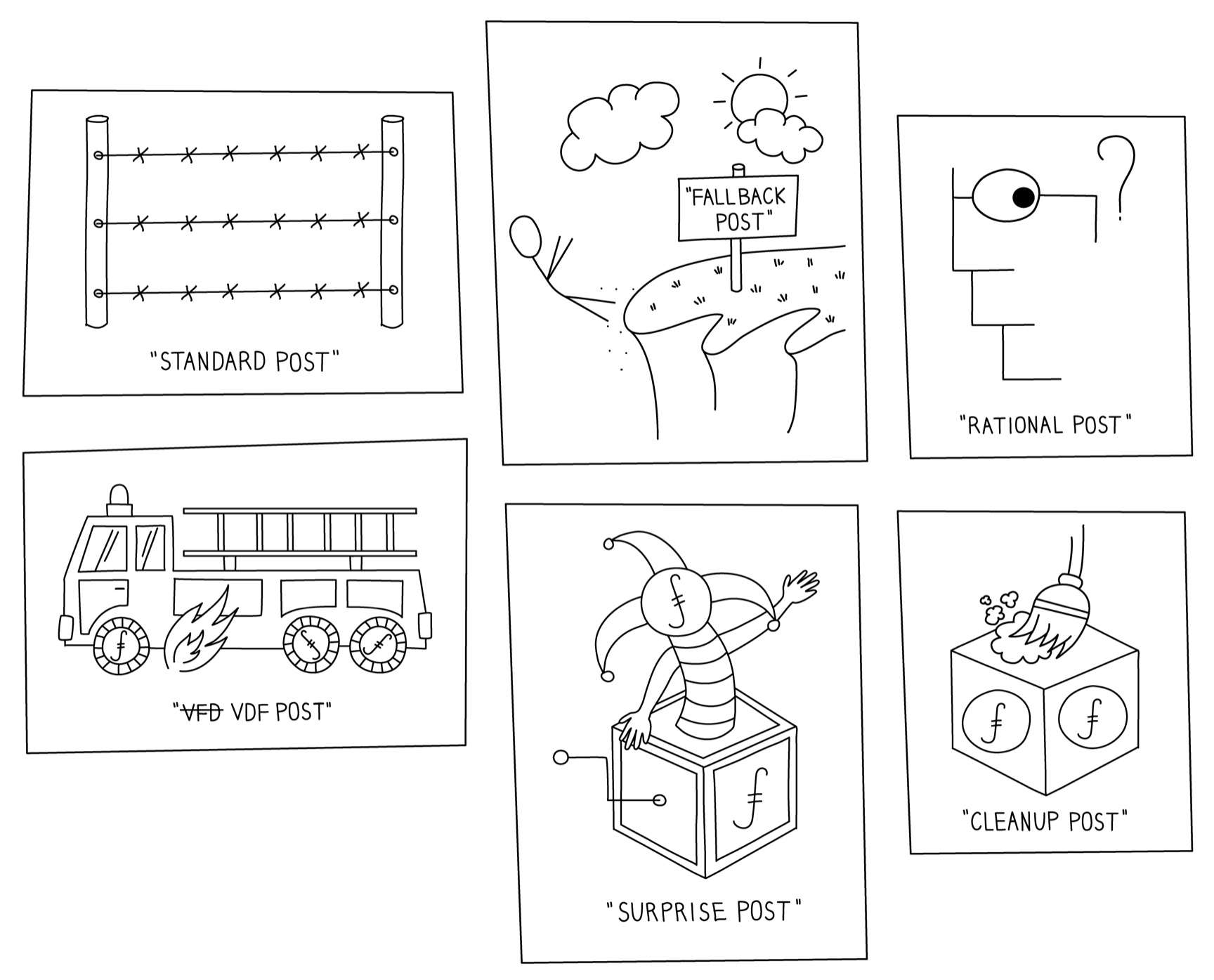

A great story about all of this work is what we call the proofs rollercoaster. You end up creating tons of different constructions over time, with all these different parameters serving all these different use cases.

This parameter choice, over the choice of proofs in Filecoin has been probably the biggest reason it’s taken us so long to ship all of this stuff. Because you choose one construction and it has a certain shape and produces artifacts of a particular size, and maybe that’s fine, and then you tweak some parameter, like, “Hey, maybe we want the sectors to be slightly bigger.” That makes some other parameter have to change.

So pretty quickly you’re in a very large parameter space with many different variables where you tweak one thing here, and a bunch of other things have to change as well. Doing that complexity management, as a bunch of these algorithms are getting optimized, is pretty difficult. Because a lot of these constructions, these slow encodings, you want slow enough to be useful for the proof but fast enough so that it’s not very expensive. Dialing that so that it’s just right is a pretty difficult challenge, then nailing that with particular SNARK constructions on top to make sure that you can do this efficiently and succinctly enough for the chain.

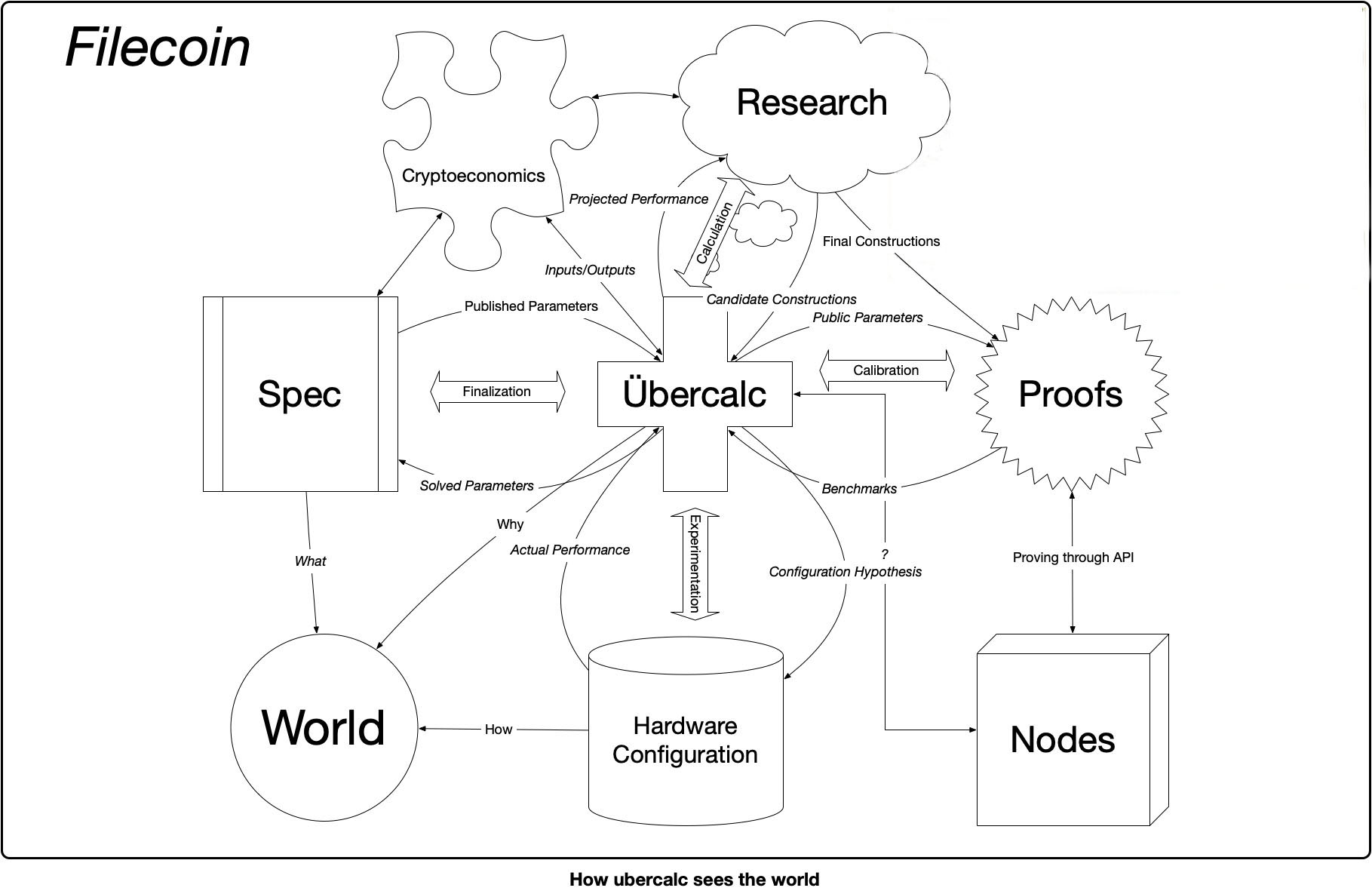

All of this parameter optimization can be so intense and difficult that we actually had to write software to be able to deal with this. We have a constraints solver just to be able to deal with the constraint optimization problem, on choosing the proof structures and the parameters in Filecoin. It’s kind of an amazing result out of this, other groups can now use that to make their lives easier, but we had to write this.

We used a tool called Orient, it’s on GitHub and everything is open source (See Filecoin’s parameters in Orient and the Übercalc). It has a special language where you define a particular algorithm and the artifacts they generate, then compose them into larger ones, with all these variables and parameters.

And then you can do experimental results for say, how long certain hash functions take, and plug that data in some of the parameters and compute out what some of the other parameters have to be. So, for example, based on this hash function and how long that takes, inside of the SNARK or outside of a SNARK, then this particular construction is the one you want to use, because it minimizes some times or minimizes some on-chain footprint and all of that stuff is calculated through this solver.

Making blockchain technology right now, because of how complex the structures are, both the individual primitives and how they’re weaved into the chain, and all the off-chain protocols and so on, all of that stuff is so complex, that we need this software to help us write software. Similar to how chip manufacturing where, chip manufacturing was going pretty well until it hit a certain density, and they then stopped being able to produce chips manually. They had to start using software to be able to lay out the chips. I think we’ve hit that point with blockchains, where some of the constructions we’re making, we need software to help us design.

Making blockchain technology right now, because of how complex the structures are, both the individual primitives and how they’re weaved into the chain, and all the off-chain protocols and so on, all of that stuff is so complex, that we need this software to help us write software. Similar to how chip manufacturing where, chip manufacturing was going pretty well until it hit a certain density, and they then stopped being able to produce chips manually. They had to start using software to be able to lay out the chips. I think we’ve hit that point with blockchains, where some of the constructions we’re making, we need software to help us design.

I think no other network is using Proof of Replication, it’s an advantage we have that we created that field. So that’s one differentiating factor. We are also the only one with this fluid market structure that is meant to be optimized based on an ask and bid structure where miners and clients are able to reason about prices together and then form deals out of that. I think we are also the only ones doing consensus backed by useful storage. With other networks it may be a consensus backed by a Proof of Space, but in our case it’s useful. Those are the three biggest differentiating factors of Filecoin.

Then there’s the tight integration through libp2p into IPFS and a bunch of other things where there’s a ton of usage on IPFS already. It’s going to be easy to backup all of that data straight into Filecoin. One cool thing to mention is that IPFS is an open network and we’ve seen other networks start to add support for it which is also really cool to see. It’s meant to be a decoupled layer for that reason.”

Juan Benet’s full interview on the Zero Knowledge podcast can be found here.